A Cognitive Security Analysis of Foreign-Origin Influence Operations Exposed by Platform Transparency

The Global Polarization Industrial Complex

Abstract

The digital information environment, often conceptualized as the modern “public square,” relies fundamentally on the presumption of authentic human interaction. However, in late November 2025, a transparency feature introduced by the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) shattered this presumption for a significant segment of the American political internet. The feature, designed to display the country of origin for user accounts, inadvertently revealed that a substantial number of high-profile, hyper-partisan influencer accounts, specifically those aligned with the “Make America Great Again” (MAGA) movement, were operating not from the United States, but from jurisdictions such as Nigeria, Vietnam, Thailand, Russia, and Georgia (Editor and Publisher, 2025).

This paper provides a comprehensive cognitive security analysis of this event. It argues that the exposure of these accounts validates the thesis of the “Cognitive Attack Surface,” which highlights the vulnerability of the human mind to manipulation through digital vectors (Rohleder, 2025). While historical analysis of foreign influence has focused heavily on state-sponsored actors like Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA), the data revealed by X suggests a paradigm shift toward a decentralized, commercialized model of “engagement farming.” In this new economy, foreign actors exploit the cognitive vulnerabilities of American citizens not necessarily for ideological conquest, but for financial incentives enabled by platform monetization schemes (Influencer Marketing Hub, 2025).

The following analysis synthesizes data from the X transparency rollout, academic research on click-farms, social media, the outrage economy, attack vectors, and cognitive science. It details the specific networks exposed, examines the economic incentives driving the “populist disinformation doom loop,” and explores the geopolitical implications of “digital mercenaries” simulating American political discourse. Ultimately, it posits that the greatest threat to democratic cohesion is no longer solely the foreign state adversary, but the algorithmic commodification of domestic rage, which allows commercial actors in the Global South to monetize the polarization of the Global North.

Introduction: The Transparency Paradox and the Crisis of Authenticity

In the contemporary digital age, the integrity of information systems is paramount to national security. Yet, unlike traditional cybersecurity, which protects hardware and networks, “cognitive security” is concerned with protecting the integrity of human thinking itself (Rohleder, 2025). The events of late November 2025 serve as a stark illustration of how fragile this security has become.

The Rollout of the “About This Account” Feature

On the weekend of November 24, 2025, X deployed a new interface element aimed at bolstering platform transparency. Spearheaded by Nikita Bier, X’s Head of Product, the “About This Account” feature allowed users to view granular metadata regarding any profile, most notably the country or region where the account was based (Anadolu Agency, 2025). The stated objective was to empower users to verify the authenticity of the voices they engaged with in the “global town square” and to curb the influence of automated bot networks and troll farms (Cybernews, 2025).

The implementation of this feature, however, yielded immediate and unintended consequences. Instead of merely highlighting spam bots, the tool exposed the foreign origins of key influencers within the American right-wing digital ecosystem. Users who navigated to the profiles of prominent “patriotic” voices, including accounts that utilized American flag imagery, referenced the US Constitution, and employed the vernacular of the American heartland, were greeted with location tags indicating origins in Lagos, Nigeria; Tbilisi, Georgia; and Bangkok, Thailand (The Hindu, 2025).

The Scope of the Exposure

The revelations were not isolated incidents but appeared to represent a systemic infiltration of the MAGA (Make America Great Again, pro-Trump movement) online community by foreign actors. Self-identified Liberal commentators, who had long hypothesized that the scale of online right-wing support was artificially inflated, viewed the data as vindication. Influencer Harry Sisson described the event as “one of the greatest days on this platform,” citing the exposure of accounts like @MAGANationX (Eastern Europe) and @IvankaNews (Nigeria) as proof of foreign manipulation (The Guardian, 2025).

However, the exposure was not politically unidirectional. While the volume of exposed high-profile accounts skewed heavily toward the pro-Trump ecosystem, the transparency tool also flagged the account @RepublicansAgainstTrump, which is a massive anti-Trump page with over one million followers, as operating out of Austria (Hindustan Times, 2025). This finding complicates the narrative, suggesting that the vulnerability to foreign influence is not a partisan defect but a systemic feature of the polarized American digital landscape.

The Technical Controversy and the “Glitch” Narrative

The rollout was immediately beset by technical disputes that allowed some actors to claim plausible deniability. The most significant controversy involved the official account of the US Department of Homeland Security (@DHSgov), which briefly displayed a location tag of “Israel” (Anadolu Agency, 2025). This anomaly fueled immediate conspiracy theories regarding foreign control of the US government.

Nikita Bier and X engineering teams scrambled to address these discrepancies, attributing them to “rough edges” in the geolocation database and the complexities of IP address allocation (Anadolu Agency, 2025). Furthermore, the widespread use of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) by privacy-conscious users meant that some legitimate American users appeared to be abroad, while sophisticated foreign actors could mask their true location. Vitalik Buterin, the co-founder of Ethereum, criticized the feature as a security risk that could “dox” innocent users in repressive regimes, highlighting the tension between transparency and privacy (Cryptonews, 2025). Despite these technical caveats, security researchers argued that the clustering of political influencer accounts in known commercial click-farm hubs (like Nigeria and Vietnam) was statistically significant and unlikely to be the result of random technical glitches (The Hindu, 2025).

Theoretical Framework: The Cognitive Attack Surface

To understand why foreign actors can so easily infiltrate domestic political discourse, we must look beyond technology to the evolutionary architecture of the human mind. As detailed in the book Cognitive Attack Surface, the human mind possesses inherent vulnerabilities that are particularly maladaptive in the digital age (Rohleder, 2025).

The Evolutionary Roots of Cognitive Vulnerabilities

The human brain evolved to process information within small, tight-knit hunter-gatherer tribes. In this ancestral environment, survival depended on rapid pattern recognition, deference to authority figures, and strict adherence to group norms (Rohleder, 2025). These evolutionary pressures selected for specific cognitive shortcuts, or heuristics, which now serve as backdoors for digital manipulation.

The “Mismatch Hypothesis” suggests that our “stone-age” brains are fundamentally ill-equipped to handle the complexity and scale of the modern information environment (Rohleder, 2025). We are wired to trust the “evidence of our eyes,” meaning that when we see a profile picture of a person who looks like us, utilizing our cultural symbols (flags, slogans), our “System 1” (fast, intuitive) thinking automatically categorizes them as “friend” or “in-group” (Rohleder, 2025). Foreign actors exploit this by engaging in “mimicry,” adopting the visual and linguistic markers of the target tribe to bypass the brain’s skepticism (slower logical System 2 thinking).

Tribalism as a Primary Exploit

Tribalism is perhaps the most potent cognitive vulnerability exploited in these operations. Social Identity Theory posits that individuals derive a significant portion of their self-esteem from their group membership (Rohleder, 2025). Consequently, humans are biologically predisposed to defend their “in-group” and derogate the “out-group.”

The Nigerian and Eastern European accounts exposed by X engaged in “identity weaponization” (ResearchGate, 2025). They did not present nuanced policy arguments; rather, they trafficked in the absolute markers of tribal identity. By constantly reinforcing the “Us vs. Them” narrative, thus framing political opponents not as rivals but as existential threats, these accounts activated the “tribal identity strategic optimizers” (strategic algorithms in our brain that optimize for a goal or outcome) in their audience’s brains (Rohleder, 2025). Once these optimizers are triggered, the brain prioritizes group loyalty over epistemic accuracy, making the user willing to accept, share, and defend information even if it is dubious, simply because it signals allegiance to the tribe.

Confirmation Bias and the Echo Chamber

The mechanism that sustains these foreign operations is confirmation bias, which is the tendency to search for, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs (Rohleder, 2025). The foreign accounts act as “echo chamber facilitators.” They provide the affirmation that the user subconsciously craves.

When a user in the American Midwest feels marginalized or unheard, finding an account like @MAGANationX (secretly run from Russia) that validates their worldview creates a powerful dopamine response (Rohleder, 2025). The user does not scrutinize the source because the content feels emotionally “true.” This feeling of truthfulness, combined with the algorithmic reinforcement of social media platforms, creates an “echo chamber of the mind,” where the user is insulated from contradictory evidence. The foreign operator effectively outsources the maintenance of the delusion to the victim’s own cognitive machinery (Rohleder, 2025).

The Illusion of Explanatory Depth

Another relevant cognitive phenomenon is the “illusion of explanatory depth,” where individuals overestimate their understanding of complex systems (Rohleder, 2025). Foreign accounts reinforce this illusion by offering simplistic, conspiratorial narratives to explain complex geopolitical or economic events. By reducing complex reality to a struggle between “Patriots” and the “Deep State,” these accounts provide cognitive closure to anxious users. The exposure of the accounts’ foreign origins threatens this closure, inducing cognitive dissonance. However, because the narrative provides a sense of order and control, users often fight to preserve the delusion rather than accept the chaotic reality that their “community” is a fabrication (Rohleder, 2025).

Anatomy of the Inauthentic: A Typology of Exposed Networks

The X transparency feature did not reveal a monolith of foreign influence but rather a diverse ecosystem of actors with varying motivations and tactics. By analyzing the data from the exposure, we can categorize these actors into distinct clusters based on their geographic origin and operational behavior.

The Nigerian Cluster: The Engagement Arbitrageurs

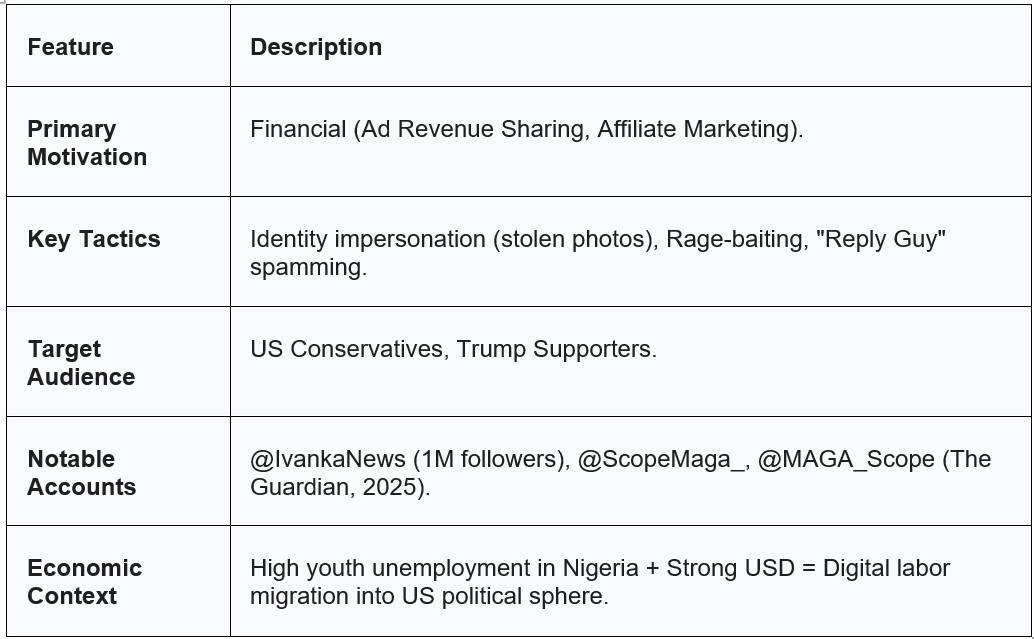

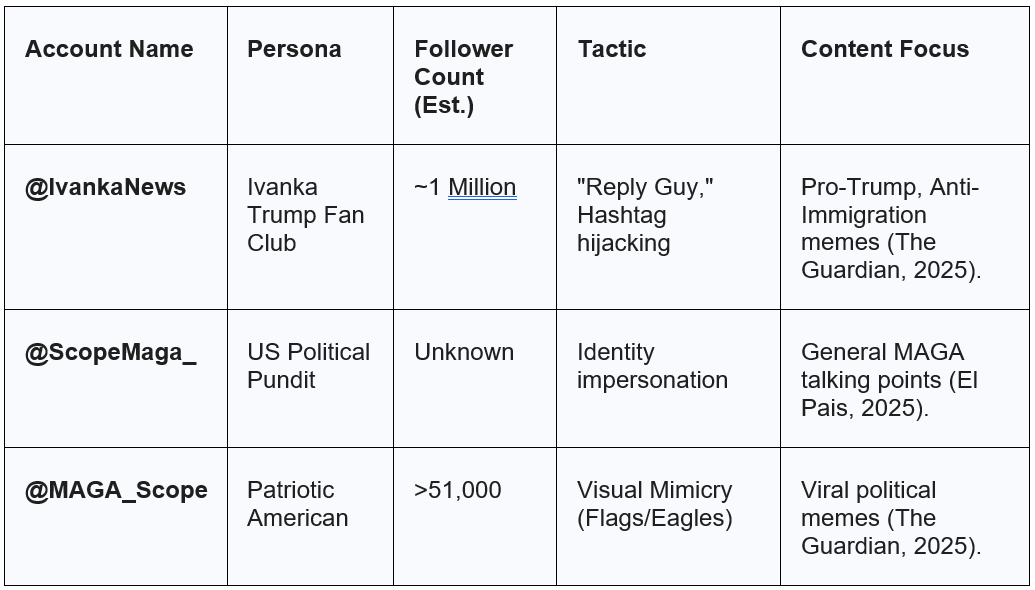

One of the most surprising revelations was the sheer volume of high-profile “MAGA” accounts operating out of Nigeria. Accounts such as @IvankaNews, @ScopeMaga, and @MAGA_Scope were found to be based in this West African nation, despite posing as fervent American patriots (The Guardian, 2025).

The primary driver for this cluster appears to be economic rather than ideological. Nigeria has a large, English-speaking population with high digital literacy but limited economic opportunities and a weak currency relative to the US dollar (TechTrendsKE, 2025). This creates a powerful incentive for “engagement arbitrage.” The X “Ads Revenue Sharing” program, introduced in 2023, pays creators based on the verified engagement (ads viewed in replies) their posts generate (Influencer Marketing Hub, 2025). Since US-based engagement commands a higher “Cost Per Mille” (CPM) from advertisers, Nigerian operators have a financial incentive to curate content that appeals to American audiences.

Table 1: Profile of the Nigerian Engagement Cluster

The tactic of choice for this cluster is “identity theft.” Investigations by the Centre for Information Resilience (CIR) revealed a network of accounts posing as young, attractive, pro-Trump American women using photos stolen from European fashion influencers (The Hindu, 2025). For example, the account “Eva_maga1996” used photos of a Danish influencer, editing “MAGA” slogans onto her clothing. This exploits the “Halo Effect,” where physical attractiveness is unconsciously associated with trustworthiness and moral goodness (Rohleder, 2025).

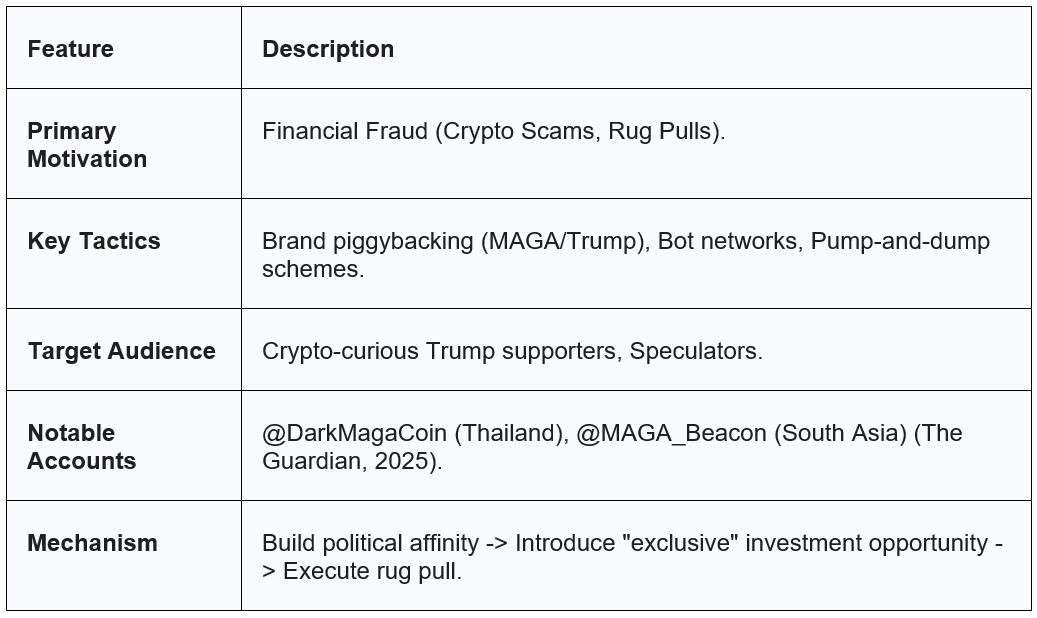

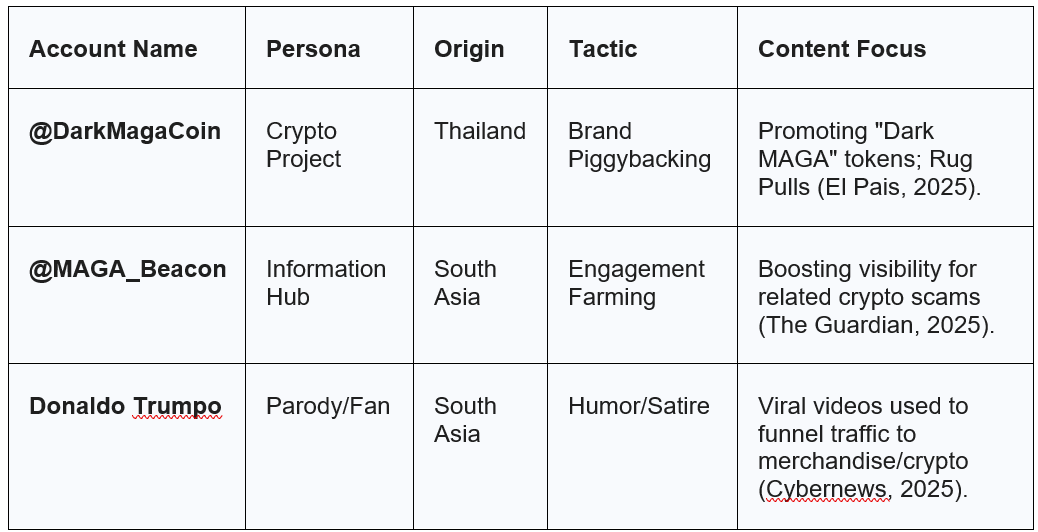

The Southeast Asian Cluster: Crypto-Political Scams

A second distinct cluster originated in Southeast Asia, specifically Thailand, Vietnam, and portions of India/Bangladesh. Accounts like @DarkMagaCoin (Thailand) and @MAGA_Beacon (South Asia) represent a convergence of political polarization and financial fraud (The Hindu, 2025).

This cluster utilizes the MAGA brand not just for ad revenue, but as a marketing vehicle for cryptocurrency scams, specifically “meme coins” and “rug pulls” (Coinbase, 2025). The “Dark MAGA” aesthetic, which is characterized by red and black imagery and “laser eyes”, is co-opted to sell tokens like “Dark MAGA Coin” or “TrumpCoin” (Coinbase, 2025). The operators build trust through political agreement and then leverage that trust to solicit investment.

Table 2: Profile of the Southeast Asian Crypto Cluster

This cluster highlights the intersection of “greed optimizers” and “tribal identity optimizers” (Rohleder, 2025). The victims are lured in by the promise of wealth (greed) but let their guard down because the solicitation comes from a perceived member of their political tribe.

The Eastern European Cluster: Ideological Hybrid Warfare

The third cluster, emanating from Russia, Georgia, and Eastern Europe, represents the most traditional form of foreign influence, though it too has adapted to commercial incentives. The exposure of @MAGANationX (Eastern Europe) aligns with historical patterns of Russian interference, such as the operations of the Internet Research Agency (IRA) (The Guardian, 2025).

Unlike the Nigerian or Thai clusters, which focus on generic engagement or quick financial scams, this cluster often traffics in deeper, more sophisticated disinformation narratives. They promote divisive conspiracy theories (e.g., QAnon, election fraud) that are designed to erode trust in democratic institutions over the long term (DemTech, 2021). While they may also monetize via X’s revenue sharing, their primary utility is often strategic destabilization. The “About This Account” feature revealed that despite years of sanctions and platform crackdowns, these actors remain embedded in the US digital ecosystem, constantly evolving their tactics to evade detection.

The Political Economy of Rage: The “Populist Disinformation Doom Loop”

The most significant insight from the X location exposure is the realization that political polarization is now a global commodity. The interaction between platform monetization algorithms and foreign economic disparities has created a self-sustaining cycle we can term the Populist Disinformation Doom Loop.

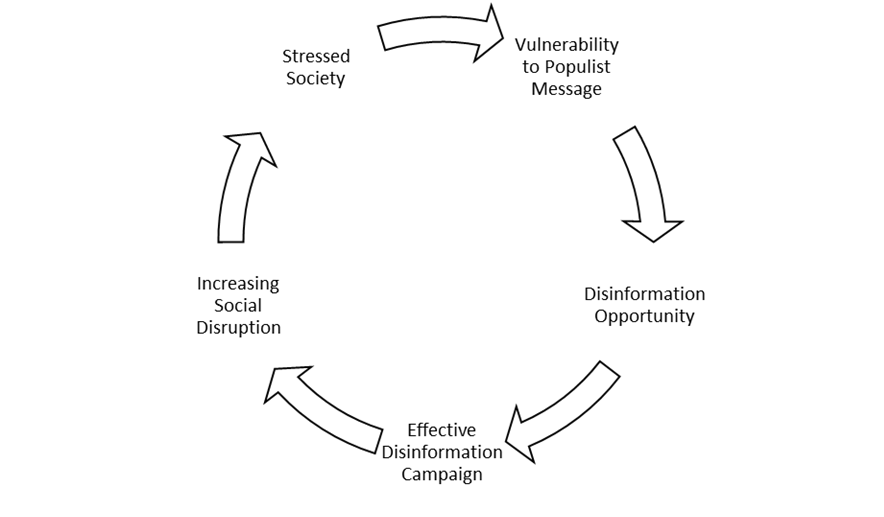

The Mechanism of the Loop

This loop operates on a sequential feedback mechanism as defined in Cognitive Attack Surface (Rohleder, 2025). It does not merely cycle through rage but systematically deepens societal fragility:

1. Vulnerability to Populist Message: The cycle begins with a population already suffering from economic anxiety or cultural displacement, creating an initial susceptibility to populist rhetoric.

2. Disinformation Opportunity: The populist narrative vulnerability creates a opportunity for bad actors (both foreign and domestic).

3. Effective Disinformation Campaign: Foreign operators (e.g., the Nigerian or Russian clusters) step in to fill this gap with “rage bait” and identity-affirming fabrications. Because the audience is primed, these campaigns effectively bypass critical thinking.

4. Increasing Social Disruption: The spread of this disinformation exacerbates tribal divisions, erodes trust in shared institutions, and fragments reality.

5. Stressed Society: The resulting disruption weakens the social fabric and economic stability, increasing the overall stress level of the society.

6. Loop to Beginning: This heightened societal stress leads back to Step 1, creating an even deeper Vulnerability to Populist Message, thus restarting the cycle with greater intensity.

Populist Disinformation Doom Loop

Economic Arbitrage as a Security Threat

The disparity in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) between the US and the Global South is a critical weakness in the global security landscape. For a user in the United States, $500 a month from X revenue might be a nice side income. For a user in Nigeria or Vietnam, where the cost of living is significantly lower, earning $500 USD a month can be a life-changing, upper-middle-class income (TechTrendsKE, 2025).

This economic reality ensures a limitless supply of labor for engagement farming. As long as US platforms pay in strong currency for engagement, “digital mercenaries” will continue to mine the cognitive vulnerabilities of Americans. The ideology is secondary to the payout; if “Leftist Rage” paid better, these same farms would pivot to producing Left-Winged content. The vulnerability lies in the platform’s incentive structure, which rewards friction over fact.

The Role of “Dark Patterns” and Platform Design

Platform design choices, also known as “Dark Patterns,” facilitate this exploitation. The removal of friction from the sharing process (e.g., one-click retweets) and the algorithmic prioritization of emotionally charged content create an environment where “slow thinking” (System 2) is suppressed (Rohleder, 2025). The X Premium “Blue Check” is a particularly potent dark pattern in this context. Historically, a signifier of identity verification, it is now a purchasable commodity. Foreign actors invest in these checks not just for the algorithmic boost, but to exploit the “Authority Bias” of users who still associate the checkmark with credibility (Mashable, 2025). This commodification of trust signals has lowered the barrier to entry for impostors.

Geopolitical Implications: From Active Measures to Digital Mercenaries

The landscape of foreign influence has evolved from the centralized “Active Measures” of the Cold War to a chaotic marketplace of “Digital Mercenaries.” This shift complicates attribution and defense strategies for national security apparatuses.

The Blurring of State and Non-State Actors

The X platform exposure highlights the difficulty in distinguishing between state-sponsored disinformation and commercial click-farms. A click-farm in Vietnam promoting anti-vaccine narratives to sell supplements might inadvertently advance the geopolitical goals of a state adversary like China or Russia (DemTech, 2018). Furthermore, state actors often employ these commercial firms as proxies to maintain plausible deniability. The “Spamouflage” network, linked to the Chinese state, has been documented using similar tactics of impersonating US voters to push divisive narratives (Graphika, 2025).

The existence of a commercial market for disinformation means that state actors no longer need to build all capabilities in-house; they can simply hire existing infrastructure in the Global South to amplify their messages. This “Disinformation-as-a-Service” model allows for rapid scaling and makes the “attribution problem” in cyber warfare nearly insoluble (ISD, 2025).

The “Reverse Cargo Cult” of Democracy

The phenomenon of foreign actors mimicking American political discourse represents a “Reverse Cargo Cult.” In traditional cargo cults, groups mimic the superficial forms of a more technologically advanced society in hopes of receiving material goods. Here, foreign actors are mimicking the dysfunction of American democracy, including its polarization, its vitriol, and its conspiracy theories, because that is what the American technology platforms reward with capital.

This dynamic suggests a grim geopolitical reality: the United States is exporting its own sociopolitical decay as a template for the global digital economy. By incentivizing the simulation of hyper-partisanship, US platforms are training a generation of global digital workers in the arts of cognitive manipulation and democratic destabilization.

The “Dead Internet” Theory and Epistemic Insecurity

The revelation that so many “Americans” online are actually foreign operators lends credence to the “Dead Internet Theory”, which is the hypothesis that a vast proportion of internet activity is bot-generated or inauthentic (EM360Tech, 2025). For the average citizen, this realization fosters “epistemic insecurity”; a deep-seated anxiety that nothing online can be trusted.

This erosion of trust is a primary goal of “cognitive warfare” (PMC, 2025). When citizens cannot distinguish between a genuine compatriot and a Nigerian bot, they retreat into smaller, more radicalized trust networks, further fragmenting the social fabric. The “Global Town Square” ceases to function as a space for discourse and becomes a hall of mirrors, reflecting distorted realities back at the user.

Strategic Mitigation and Policy Recommendations

Addressing the industrialization of influence operations requires moving beyond “media literacy” to structural interventions in platform design and policy. The following strategies prioritize “Information Assurance” thus ensuring the integrity and authenticity of the information ecosystem.

Platform Governance: Identity and Geographic Verification

The anonymity of the web, while important for free speech, has been weaponized to allow foreign actors to impersonate domestic political constituents at scale. Platforms must implement tiered identity verification standards.

“Know Your Customer” (KYC) for High-Reach Accounts: Social media platforms should adopt financial industry KYC standards for accounts that achieve a certain threshold of reach (e.g., 100,000 followers) or participate in ad revenue sharing. This would require the submission of government-issued identification to verify the identity and location of the operator.

Geographic Provenance Labels: The “About This Account” feature should be mandatory and persistent for accounts engaging in political discourse. Accounts operating from outside the target country of their content should carry a visible “Foreign Origin” tag to reduce the efficacy of deceptive mimicry.

Verified Identity Credentialing: Platforms should distinguish between “paid verification” (e.g., Twitter Blue) and “identity verification.” A badge indicating that a user’s government ID and location have been confirmed would restore the “Authority Bias” to legitimate actors rather than impostors.

Economic Disincentives: Breaking the “Doom Loop”

The primary driver for the exposed Nigerian and Southeast Asian networks is financial, not ideological. Policy mitigation must effectively target the incentive structure.

Demonetization of Polarization: Ad revenue sharing algorithms must be adjusted to exclude content flagged for high-velocity misinformation or inauthentic behavior. If “rage bait” ceases to be profitable, commercial click-farms will pivot to other verticals.

Algorithmic Transparency: Platforms must be transparent about how engagement metrics (likes, retweets) influence visibility. Down-ranking content that exhibits “coordinated inauthentic behavior” (CIB) or originates from known VPN endpoints associated with click-farms can artificially suppress the virality of foreign disinformation.

Transnational Regulatory Frameworks

Self-regulation by platforms has proven insufficient. Legislative frameworks are necessary to enforce transparency standards.

Modernizing FARA: The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) should be updated to explicitly cover “digital mercenaries”—foreign commercial actors who attempt to influence US political processes for profit, regardless of state sponsorship (American Promise, 2023).

Cross-Border Data Sharing: Establishing a transnational oversight body to share real-time intelligence on click-farm signatures and bot network behaviors can help platforms identify and ban actors jumping between jurisdictions.

The Global Polarization Industrial Complex

The exposure of the foreign-run MAGA networks on X was a watershed moment for cognitive security. It peeled back the layers of the digital culture war to reveal a machinery that is less ideological than it is industrial. The outrage that fuels American polarization is being manufactured on assembly lines in Lagos, Ho Chi Minh City, and St. Petersburg, packaged in the guise of patriotism, and sold back to the American public in exchange for ad revenue.

This phenomenon represents the industrialization of the “Cognitive Attack Surface.” Bad actors have successfully monetized the evolutionary glitches of the human mind—our tribalism, our fear, our need for validation. The defense against this threat cannot be solely technological; it must be cognitive and structural. It requires a collective awakening to the reality that in the digital age, our attention is a currency, and our anger is a product. To reclaim our cognitive liberty, we must stop buying what they are selling.

Detailed Network Analysis: Profiles of Inauthenticity

To provide a granular understanding of the threat landscape, this section details specific networks exposed by the X transparency feature.

The Nigerian Engagement Cluster

Primary Motivation: Economic (Ad Revenue Arbitrage).

Operational Security (OPSEC): Low. Often use real IP addresses, leading to easy detection.

Table 3: Key Accounts in the Nigerian Network

Insight: This cluster represents the “gig economy” of disinformation. These are likely young, digitally savvy individuals leveraging the global nature of X to earn a living. Their content is derivative, often copying successful posts from real US users to guarantee engagement.

The Southeast Asian Crypto-Political Complex

Primary Motivation: Financial Fraud (Crypto Scams).

Operational Security: Moderate. Use of botnets and automated scripts.

Table 4: Key Accounts in the Southeast Asian Network

Insight: This cluster is dangerous because it directly extracts wealth from the target demographic. By embedding financial scams within political affinity groups, they bypass the skepticism usually applied to financial solicitations.

The Counter-Example: The Austrian Anti-Trump Node

Primary Motivation: Ideological/Commercial Mix.

Account: @RepublicansAgainstTrump (Hindustan Times, 2025).

Origin: Austria.

Insight: This example demonstrates that foreign influence is not exclusive to pro-Trump right campaigns. High-engagement political content, regardless of alignment, attracts foreign operators. It validates the idea that in some cases polarization itself is the commodity, not a specific ideology.

Second-Order Implications

The End of “Location” as a Trust Metric

The immediate workaround for these click-farms is the adoption of residential US proxies and VPNs. The X feature, while revealing, likely signaled the end of the “easy era” of detection. Future detection will require behavioral analysis (time of day posting, linguistic syntax errors) rather than simple metadata (Cloudwards, 2025).

The AI Multiplier

The integration of Generative AI (LLMs) into these farms will drastically increase their effectiveness. AI can generate perfect, idiomatic English, create culturally specific memes, and interact in comments without the “broken English” tells of the past (IC3, 2025). This will make the “Turing Test” for political authenticity nearly impossible to pass for the average user.

The Moral Hazard of Algorithms

The existence of these farms is a direct indictment of the “engagement-based” algorithmic model. As long as platforms prioritize “time on site” and “reply volume,” they will inevitably incentivize the creation of rage bait. The solution requires a fundamental rethinking of how information is sorted and valued, shifting from “popularity” to “integrity” or “veracity” (AEA, 2025).

Individual Call to Action

The revelation of the “Foreign MAGA” networks is a warning. It illuminates the extent to which our domestic political reality has been colonized by foreign commercial interests.

Safety Tips and Call to Action:

1. Verify: Do not accept an account’s bio as truth.

2. Pause: Engage System 2 thinking before sharing outrage.

3. Defund: Do not engage with rage bait. Starve the farms of their revenue.

The battle for attention, belief, and identity is the defining conflict of our time. It is a battle not for territory, but for the mind itself. This is how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a twitter.

References

AEA. (2025). Report on the Status of Social Media Use in Economics and Recommendations for Best Practices. American Economic Association.

American Promise. (2023). Foreign Money Report.

Anadolu Agency. (2025, November 25). X location feature reveals some MAGA accounts abroad, sparking online debate.

Centennial World. (2025). The Rise of Ragebait: From Bizarre Influencer Lies to Insidious Political Strategies.

CFR. (2025). Foreign Influence and Democratic Governance. Council on Foreign Relations.

Cloudwards. (2025, November 25). X Plans to Test, Show User Location Data or VPN Use.

Coinbase. (2025). Convert Spiking SPIKE to BOOK OF RUGS.

Cryptonews. (2025, November 25). Vitalik Buterin Warns X’s Location Feature Creates ‘Easy to Fake’ Security Risk.

Cybernews. (2025, November 25). Elon Musk’s new X feature exposes MAGA accounts as “foreign trolls”.

DemTech. (2018). Challenging Truth and Trust: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute.

DemTech. (2021). Industrialized Disinformation: 2020 Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute.

Editor and Publisher. (2025, November 25). New X feature exposes foreign pro-MAGA accounts.

El Pais. (2025, November 25). X’s new location feature raises questions about the origin of some MAGA accounts.

EM360Tech. (2025). What is Cognitive Hacking? The Cyber Attack That Targets Your Mind.

Graphika. (2025). The #Americans.

Hindustan Times. (2025, November 25). X’s new country-of-origin feature shakes MAGA and Democrat circles as many ‘US’ accounts revealed to be foreign-run.

IC3. (2025). Just So You Know: Foreign Threat Actors Likely to Use a Variety of Tactics to Develop and Spread Disinformation During 2024 U.S. General Election Cycle. Internet Crime Complaint Center.

Influencer Marketing Hub. (2025). X (Twitter) Ads Revenue Sharing: Eligibility & Payout Math.

ISD. (2025). Commercial Disinformation. Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

Mashable. (2025, November 25). Fake news tweets take off as Twitter blue checks go up for sale.

Outfy. (2025). How to Make Money on X (Twitter) in 2025: Complete Guide.

PMC. (2025). The history of the semantic hacking project and the lessons it teaches for modern cognitive security. PubMed Central.

Precedence Research. (2025, November 25). X Launches Transparency Tool to Verify Authentic Profiles.

Punch. (2025, November 25). X rolls out feature showing users’ country of origin.

ResearchGate. (2025). Ethnopolitical warfare: Causes, consequences, and possible solutions.

Rohleder, K. (2025). Cognitive Attack Surface: The Mind’s Vulnerabilities and How to Build Resilience Against Manipulation, Exploitation, and Delusion.

Scroll.in. (2025, November 25). There is a reason your X feed has turned more toxic. Have you heard of ‘engagement farming’?.

TechTrendsKE. (2025, November 25). A Simple Label on X Opened the Door to a Week of Chaos Over Who Is Posting From Where.

The Guardian. (2025, November 25). Many prominent Maga personalities on X are based outside US, new tool reveals.

The Hindu. (2025, November 25). Based in India or U.S.? Elon Musk’s X erupts over location feature.

Wikipedia. (2025). Rage-baiting.